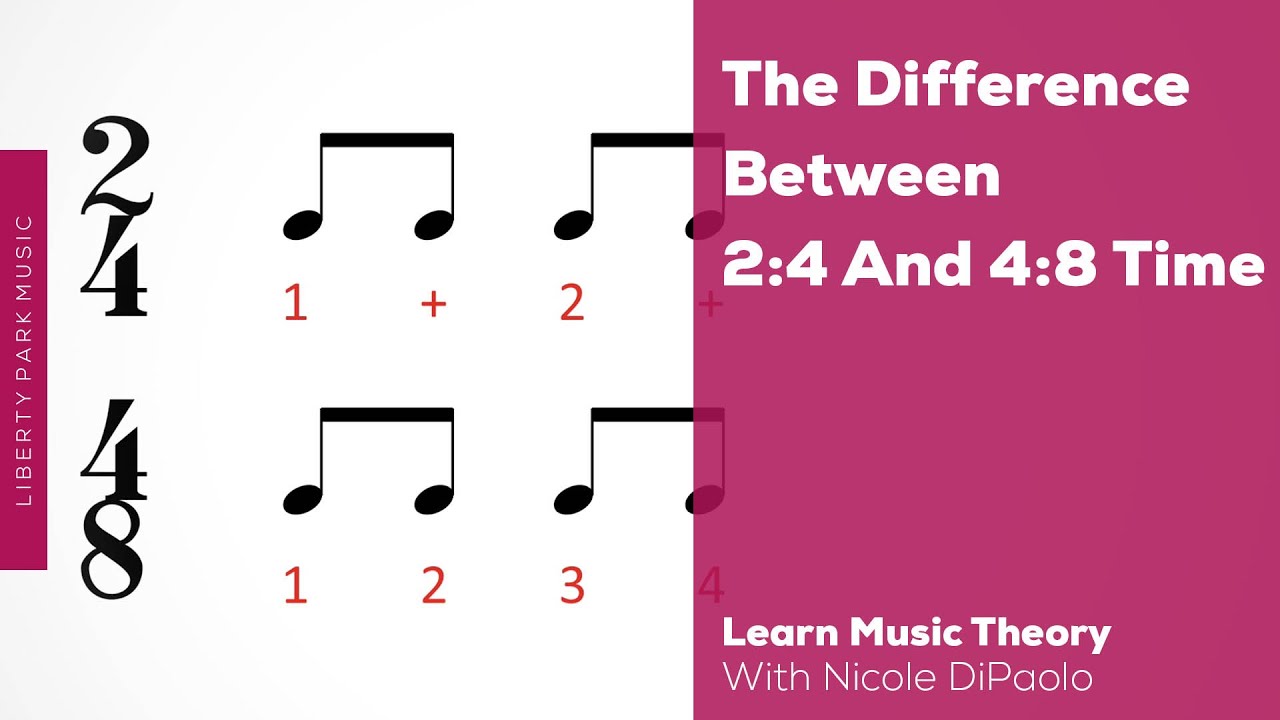

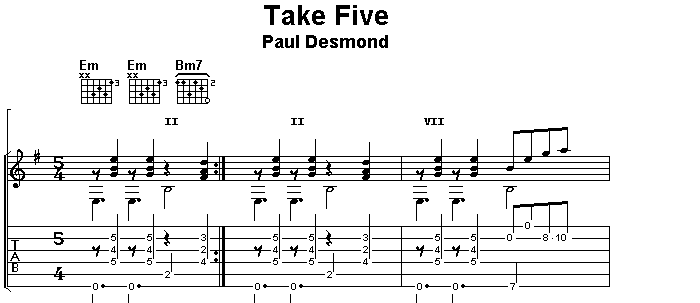

The song was composed by Paul Desmond, the Quartet’s saxophonist, and is notable for being written in 5/4 time.Īlthough some songs that use unusual or non-Western time signatures can make for odd listening, the “Take Five” is immediately likeable, with a famous saxophone riff, some funky piano chords, and a highly swung rhythm section. It is a far more cinematic and open display than what we get on the iconic “Time Out,” though not as built for posterity.“Take Five” is the biggest selling Jazz single of all time, and quite possibly the most famous Jazz song ever…

TAKE FIVE TIME SIGNATURE SERIES

Morello’s solo on the early “Take Five” unfolds in a growing series of drum rolls, flicks of the wrist that slyly alternate their frequency and then seem to pull Morello’s arms across the whole kit. Still, there is an unfolding quality on the “Outtakes” version, a sense of reaching for what’s ahead, that doesn’t pertain to the final recording, maybe because it doesn’t have to. By July, he would figure out how do far more while sounding more efficient. The “Time Outtakes” version is from June, and Morello’s part is far less developed he taps out a sparse but somewhat obtrusive pattern on the ride cymbal, trying to perch on the end of beat one and the start of beat four. It was scrapped until a session the following week, when Morello apparently nailed it in just two takes. Listening to “Time Out,” with Morello’s broad rolling beat propelling the band and his concise, dramatic solo serving as the track’s centerpiece, he is in the driver’s seat.īut on June 25, the band tried nearly two-dozen times to get the song right, and still couldn’t. Paul Desmond had written “Take Five” partly as a gesture to the quartet’s drummer, Joe Morello, who wanted to show off his newfound confidence playing in 5/4 time. The album includes five alternate versions of pieces that made it onto “Time Out” and two tracks that did not (the show tune “I’m in a Dancing Mood” and the ad hoc “Watusi Jam”). The eight tracks on “Time Outtakes” were all recorded on the first day, June 25, as the band was just breaking in the tunes. “Time Out” was recorded over three days spread across the summer of 1959. On “Time Out,” he and the quartet manage to do all this while maintaining an effortless feeling that could easily be adopted by the listener this was all the more impressive given that Brubeck was not always a graceful, mellifluous pianist. He committed himself to integrating them into his compositions, while also making sure to nest hummable melodies inside each tune. Fascinated throughout his life by rhythmic complexity, his ears were piqued during a State Department good will tour in 1958, when he heard odd-numbered folkloric rhythms in various parts of Asia. He was on tour at the time with Duke Ellington, who was clearly deserving of such an honor himself, and it was Ellington who first showed Brubeck the Time cover when it came out.Īs he built out his niche in jazz, Brubeck found purpose in a kind of globalism. Brubeck often told the story of how ashamed he had felt when, in 1954, he became the only jazz musician other than Louis Armstrong to appear on the cover of Time magazine.

They had called the pianist’s music uptight, unswinging and mannered (it often was), and some listeners rightly bridled at the injustice of how swiftly he - a white musician whose path ran through the conservatory and the college touring circuit, not the jazz clubs of New York - had vaulted over other bandleaders and into a Columbia recording contract. “Time Out” would be the achievement that effectively quieted Brubeck’s critics.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)